Prolonged Grief Disorder in the First Responder

Grieving longer than normal is associated with prolonged grief disorder.

Historically, mental health has been ignored, minimized, or downplayed at the fire chief and firefighter levels. Typical responses to feelings in the firehouse have included “suck it up, buttercup” and “leave your feelings at the door.” Thanks to generational differences, firefighters now demand mental health care and support.

Millennials and Gen Zs, in general, were raised not to be ashamed of their feelings, to voice their opinion, and ask for help. As a result, many fire departments are creating Peer Support Programs, Chaplaincy Programs, and community relationships with psychiatric hospitals and outpatient treatment providers.

The frequent flier phenomenon

The term ‘frequent flier’ brings up many emotions. It is a commonality in all fire departments worldwide. We respond to calls for service to the same people many times over months and years. Asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, CHF, mental health, and a multitude of other long-term illnesses/diseases are some of the precursors to calling 911.

After so many calls for service to the same address, it is inevitable that we begin to learn their names, love their pets, meet their neighbors, and sometimes engage with their extended family. We see them at their worst moments and provide resources, support, and often empathy for their situation. Then suddenly, one day, the calls for service to them stop. No information, no closure, and just like that, they are just a memory.

Often we’re left wondering what happened. Searching for their name up in the Obit; we wonder how the pets are and what happened to the children.

Rumination formed from unintended connections

First Responders form a connection when we find commonality with the people we serve. Maybe the lady who has fallen reminds us of a parent. The child with asthma reminds us of our child at home. A driver of the car who died may be the same age as our own child. We personalize these calls to our lives, making us question our parenting, time spent, decisions, etc. Then we ruminate about what we did or left undone.

Rumination is repetitive thinking on negative feelings and their consequences. The feelings associated with calls such as the frequent flyer and other calls for service, such as car accidents or other horrific calls with less-than-ideal outcomes, can produce many unanswered questions and the beginning of the grieving process.

Grieving defined

Grieving is the act of moving through life and adapting after a loss or traumatic situation. Grief can be experienced after an accident, new onset of mental or physical disease, loss of physical impairment, natural disasters, pandemics (Covid-19), loss of job, or ending a marriage or friendship. It is a universal feeling that crosses all boundaries of culture, age, race, and societal norms.

Grief is often confused and misdiagnosed with Depression and PTSD. Although they each share common signs and symptoms – grief is different.

Firefighters are not immune to experiencing grief and grieving. The average first responder witnesses numerous horrifying events over our career with little recovery time between calls and shifts. Many begin the grieving process after a difficult call that requires immediate lifesaving intervention, such as a fire rescue or providing medications. We begin to replay the call repeatedly in our mind, wondering if we could have done something differently.

Grieving process

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ theory on Death and Dying (1969) describes five stages of grief. Kubler-Ross’ said grieving people experience denial, bargaining, anger, depression, and acceptance.

This theory has also been extended to any loss or significant change in one’s life. For example, we might discuss a case and say things like, “I can’t believe she died so quickly; Why don’t kids wear their seatbelts; I can’t believe he died days ago, and no one noticed until now.

Adverse effects of grieving

This rumination can cause poor eating habits, reckless behavior, insomnia, sleeping too much, isolation, and the use of substances such as alcohol or drugs. These adverse effects also bleed into the firefighter’s personal life, causing stress within the family unit.

It’s not just the fire calls that cause such distress. It’s the calls and a sick parent, problems at home, financial strife, relationship problems, moving, a new baby, etc. Each of these stressors combined negatively affects us in one way or another. Checking on a patient’s outcome can provide some closure.

Normal grief responses vs prolonged grief disorder

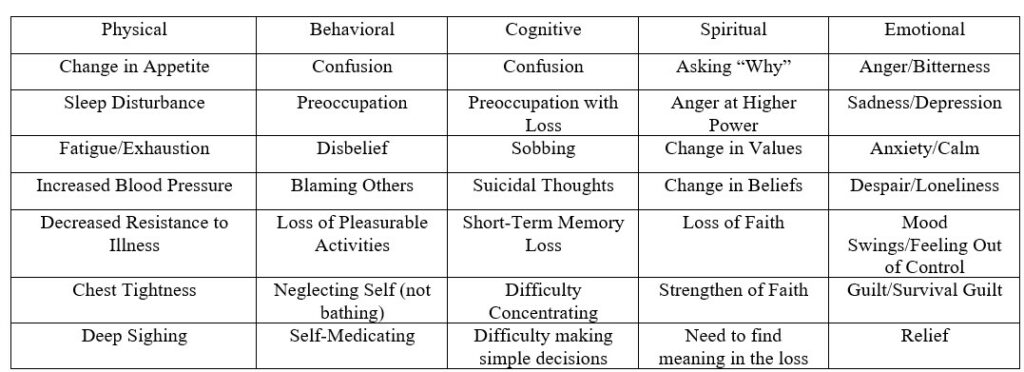

Normative response to grief includes sadness, lack of energy (anergic), changes in eating and sleeping habits, isolation, and questioning their existence (see Table 1).

Grief responses typically begin to improve within six months. When the grief responses extend past 12 months and/or after the appropriate amount of time defined by the culture, religion, societal norms, and age, Prolonged Grief Disorder may be the culprit.

Normal grief reactions can have long-term consequences on our mental and physical health if we are not careful. For example, depression and anxiety can result in isolation and losing touch with social and family support.

Appetite changes may cause physical problems such as hypertension, weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and budding eating disorders such as anorexia or binge eating.

Maladaptive coping mechanisms such as self-medication (alcohol, drugs) may cause long-term abuse and addiction resulting in loss of employment, family, and health.

Prolonged grief disorder defined

The Diagnostic Statistical Manual 5th Edition – Revised (DSM-VR) defines Prolonged Grief Disorder as being characterized by intense and persistent grief that causes problems and interferes with daily life after one year of a loved one’s death. These intense feelings can result in suicidal ideation/attempts.

At least three of the below symptomatology must be present almost every day for at least 30 days for Prolong Grief Disorder to exist.

- Identity disruption (such as feeling like part of oneself has died).

- A marked sense of disbelief about the death.

- Avoidance of reminders that the person is dead.

- Intense emotional pain (such as anger, bitterness, and sorrow) related to death.

- Difficulty with reintegration (such as problems engaging with friends, pursuing interests, and planning for the future).

- Emotional numbness (absence or marked reduction of emotional experience).

- Feeling that life is meaningless.

- Intense loneliness (feeling alone or detached from others).

How grief effects the body/brain

The study of the human brain and its ability to change and produce neuroplasticity (creating new neural pathways) has been at the forefront for many years. It should be no surprise that grief affects the human brain as well. Research by Dr. Shulman discusses the relationship between grief and the brain.

Grief causes the brain to focus on survival – fight or flight. Heart rate, blood pressure, and hormones are released and cause a change in sleep, day-to-day behaviors, memory loss, and overall bodily function.

Neuroplasticity

When we experience life-altering events, like grief, our brain compensates for the situation by creating new neural connections based on the circumstances. This is called Neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity causes the brain to adapt to new conditions, which results in resilience.

Memory loss occurs because the brain reduces nerve and brain growth to focus on survival. With each additional trauma, the nerves and brain growth diminish, affecting memory and other life skills. This process is called amygdala hijacking.

Preventing amygdala hijacking

The good news – even during traumatic times when the brain has been in survival mode, the long-term adverse effects are reversible. We must work through grief to move forward. Grief will be a forever roadblock to a healthy, functioning brain if we don’t.

Prevention is the key to minimizing amygdala hijacking. Controlling and understanding emotional reactions, practicing healthy self-care habits, and using practical coping skills can prevent Prolonged Grief Disorder and its long-lasting effects.

A psychotherapist such as an LCSW, LPC, or other licensed mental health professional can provide Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Dialectical Behavioral Theory, and other therapies to help process feelings of persistent grief.

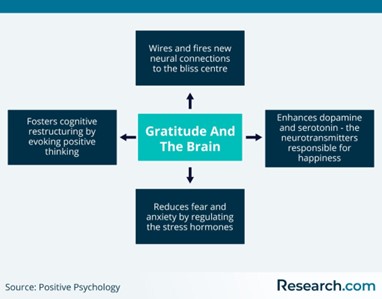

Grief support groups help battle isolation and help us feel less alone. These self-care techniques replenish our emotional bank account. Effective self-help techniques that fill our account are practicing Gratitude (Image 1), Mindfulness, Guided Meditation, Thought Reframing, trying something new, Healthy Sleep Habits, Balanced Nutrition, Exercise, and finding your purpose in this life.

Emotional drainage

Now, imagine an emotional bank account filled with time, resources, energy, happiness, rest, empathy, compassion, peace, and other emotionally sustaining things. During our life, we take it from our account daily:

- While on a call, we provide understanding and resources to families.

- In the station, we provide patience and time spent with coworkers.

- We give ourselves to our children and spouse at home emotionally and physically.

- We share time, energy, and other emotional gifts in the community.

This account is quickly emptied. Anger, sadness, resentment, and burnout fester if the account is never refilled.

Self-help techniques

Self-Help/Self-Care (Table 2) has been a buzzword for years. Libraries and bookstores have prided themselves in having an entire section dedicated to bettering ourselves. Since the creation of applications for computers and cellular phones, self-help apps have exploded. Many apps are free and provide numerous evidence-based self-help techniques. A few self-care apps are ‘Calm, Insight Timer, and I Am.’ Many more can be found in the app store or online.

Practice Yoga |

Exercise |

Declutter a Space |

Watch the Sunrise |

Plan a Getaway |

Practice Gratitude |

Get Massage |

Spend Time with Friends |

Practice Acts of Kindness |

Setting Healthy Boundaries |

Meditation |

Self- Reflection |

Identify Beliefs |

Identify Values |

Attend Worship Services |

Table 2 – Self-help techniques

Time is always a commodity in first responders’ lives. In addition to their jobs as first responders, they often have part-time jobs. Working 60-plus hours a week leaves little time and opportunity to make an appointment with a psychotherapist. Thankfully self-help books and apps are available at a moment’s notice.

My favorite self-help techniques

The following are some of my favorites:

Focusing on everything around you – being in the moment- being very aware without judgment or interpretation. If your awareness wanders, recenter your thoughts and attention. Mindfulness can be practiced almost anywhere and for any amount of time.

Negative Self-Talk is a form of self-harm. The more we talk negatively about ourselves, the brain creates stronger connections, and we begin to believe the lies. Negative thoughts such as worthlessness, lack of belief in self/abilities, and poor self-image erode self-esteem and be reinforced when problems occur.

We have thousands of thoughts each day. Making a conscious effort to challenge them is the key to a healthier self-image. We get to choose what we believe we are. We can challenge negative thoughts with questions.

For example, if I fail a math test and think I am stupid and not good at math, that will erode my self-esteem. To challenge this negative thought, we can ask ourselves two questions :

- If a friend failed a math test, would I feel comfortable telling her she is stupid and not good at math?

- What are the facts that support this negative thought?

To challenge a negative thought, instead of saying, “I am so dumb,” say, “I notice I am having thoughts that I am dumb.” Reframing thoughts change our mental state. We notice how we are feeling – not defining ourselves by our feelings.

Journaling with or without prompts is powerful. Simply writing down three good things that happened daily will reframe your mind to notice the positive. There are many available journaling prompts and ideas on the internet.

Gratitude changes our outlook on life and ourselves. It only takes a few seconds/minutes a day to practice gratitude. There are visual reminders all around us that remind us to practice gratitude. Some examples of gratitude are practicing random acts of kindness, giving people the benefit of the doubt, sleep, water, a working toilet, expanding lungs, warm coffee in the morning, and so on.

Gratitude has many evidence-based benefits. Some include lowering blood pressure, motivation, better sleeping habits, a more robust immune system, reduced jealousy, improved patience, fighting addiction, and improved mood. The list is endless.

Takeaways

- Everyone experiences grief.

- Firefighters do not discuss their feelings of grief and compartmentalize its effects.

- The normal grief response lasts about 6 – 12 months.

- Prolonged Grief Disorder is persistent grief lasting more than 12 months.

- Grief negatively affects the brain and its chemical makeup.

- Neuroplasticity allows the brain to adapt to new situations and builds new neural pathways.

- Prevention is the key to minimizing Prolonged Grief Response.

- Self-Care, Meditation, Challenging Negative Thoughts, Journaling, and Gratitude build resiliency.

- Psychotherapy and medication can help resolve grief issues and feelings of suicide.

Conclusion

Grief is a normal response to a problematic situation and loss that typically lasts six to twelve months. Experiencing physical pain, emotional distress, and questioning spirituality is part of the grief cycle. A small percentage of the grieving population experience Prolonged Grief which is more persistent and endures for more than 12 months.

Firefighters experience grief like the general population; however, the incident rate can be much higher due to the amount and type of calls. Grief affects the brain and its chemical makeup, which can affect resiliency. Self-care techniques, gratitude, Meditation, and Psychotherapy can help change and build healthier neural pathways that replenish our emotional bank account.

Resources

- Coping with Grief – IAFF

- Find a therapist

- Practice Gratitude

- Local Support Groups – Google ‘Support Groups Near Me”

References

- Shulman, L. J, MD (2021). Healing Your Brain After Loss: A Neurologist’s Perspective. (American Brain Foundation Webinar)

- Szuhany, K. L., Malgaroli, M., Miron, C. D., & Simon, N. M. (2021). Prolonged Grief Disorder: Course, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing), 19(2), 161–172.